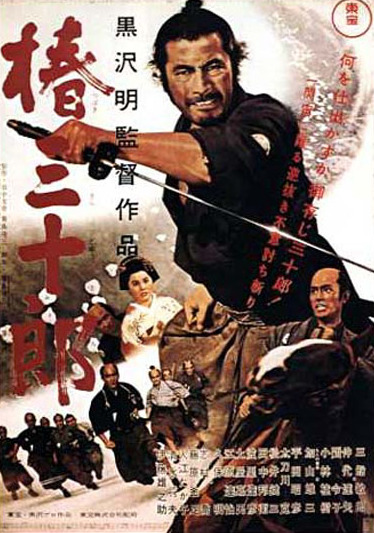

The fighting styles of Yojimbo and Sanjuro

on September 30, 2014 at 10:39 pm Much has been written about two of famed director Akira Kurosawa’s epic Samurai films Yojimbo & Sanjuro, from the look, sounds, the music, and so forth. But precious little has been done about these films and the era that they take place in.

Much has been written about two of famed director Akira Kurosawa’s epic Samurai films Yojimbo & Sanjuro, from the look, sounds, the music, and so forth. But precious little has been done about these films and the era that they take place in.

Most of Kurosawa’s films, including but not limited to the Seven Samurai, Ran

, The Lower Depths

, Kagemusha, and Throne of Blood take place in the Sengoku Period, roughly translated as the Warring States period of Japan.

What’s interesting about both Yojimbo and Sanjuro is they take place in 1860, more than 200 years later during the late Tokugawa Shogunate Period.

Let’s examine what has happened in just a few years before 1860, the year in which the film Yojimbo is set. The Edo Period in Japan’s history (also known as the Tokugawa period) brought about the end of the Sengoku period. For 200 years, an enforced period of relative peace and isolationism was brought to Japan. With no enemy army in which to wage war against, the Samurai class had no battles to fight and they mostly became local administrators. This is also the time when Bushido, the Samurai code of honor, is written down and starts to flourish amongst the monk-like soldiers, demanding a certain standard of behavior be set and applied for the warriors.[1] This code was praised in the famous incident of the 47 Samurai, a story often told and a subject that has been mined and examined to death in about any facet one could think of.

Most notably, in the year 1853 Admiral Matthew C. Perry arrived in the port of Edo, eager to open trading relations. Ignoring demands to leave, he had the large cannons on his ships begin shelling some buildings. He presented a letter from then President Millard Fillmore to the delegates of the Shogunate to open talks. He promised them after a trip to China, he would return and that he did in 1854. He found himself presented a treaty with the Japanese agreeing to virtually every demand. He presented them with a model of a steam engine and some of the cannons from ships in his fleet, showing an isolated Japan what the rest of the world had been advancing to. Isolationism was no longer a position Japan could take and change began to come quick. Expeditions from countries including Russia, England, and more were also on their way.[2]

At the beginning of Yojimbo, we see the Samurai (or more appropriately, the Ronin) who has named himself Kuwabatake Sanjuro (Mulberry field thirty-year-old) enter a town that has been overrun by two criminal kingpins, Seibei and Ushitora. It seems to be completely immune to the changes of the last 200 years and would have been a better fit in the Warring States Period. Gamblers, thieves, and criminals of all sort run riot over the town. None of them have the prowess of the blade that Sanjuro has, but the most dangerous of them all is the newly returned thug, Unosake.

At the beginning of Yojimbo, we see the Samurai (or more appropriately, the Ronin) who has named himself Kuwabatake Sanjuro (Mulberry field thirty-year-old) enter a town that has been overrun by two criminal kingpins, Seibei and Ushitora. It seems to be completely immune to the changes of the last 200 years and would have been a better fit in the Warring States Period. Gamblers, thieves, and criminals of all sort run riot over the town. None of them have the prowess of the blade that Sanjuro has, but the most dangerous of them all is the newly returned thug, Unosake.

Unosake sticks out because he has a very modern look. While his kimono is traditional to the period, he also wears a scarf, something not common to anyone else of the town or the country. Most remarkable, he brandishes a ‘new’ piece of technology no one else has: A pistol. He is the depiction of the modernization that has already started to seep into the quickly changing island nation, and Sanjuro knows from the very first sight of him that he is an agent of trouble at best, chaos at worst.

Only through his cleverness, wits, and his speed and mastery of his sword does Sanjuro triumph in the end, leaving a decimated town behind him as he walks off.

When next we see the Ronin in the film Sanjuro, he has grown by leaps and bounds not only as a swordsman but also as a person. In Yojimbo he was a master swordsman but was also portrayed as selfish, tricky and sly; an anti-hero for the ages. In Sanjuro, he has re-christened himself as Tsubaki Sanjuro (Camellia tree thirty-year-old) and has grown into himself, suggesting that the passage of a year between the making of the two films has been in keeping with the timeline of films.

We see Sanjuro as he meets with a group of youthful samurai, all of which are filled with youth and Bushido, yearning to have the honor of the mythic 47 Samurai. They condemn him for his slovenly appearance, a sight that no self-respecting Samurai of the time would have. How little do they know.

Sanjuro has changed. He uses his appearance as a weapon as much as his sword. It is because he is unconventional and has gained an insight into the human condition through time and wisdom. His character has deepened, he is a master of himself and has become a more focused warrior, able to cut through people as well as Bushido.

It is in his first sword fight of the film we see some of this growth. When Sanjuro is forced to fight a large group of samurai warriors, his first attack isn’t even with his sword.

Through a series of refined pushes and flips, he incapacitates a number of his attackers. When he finally does brandish his sword, he does not remove the blade from the scabbard. He fights the other group of samurai with a series of attacks that show a mastery of tactics.

During the course of the film Sanjuro, we see him constantly trying to mentor the young Samurai. This new and more enlightened Sanjuro must be aware of the changes coming into Japan is probably aware of the fact that much more change is to come. He sees what the future looks like, and these young Samurai, so filled with memories of centuries of battles past are looking in the wrong direction. The modernized world has reached the island’s shores and will continue to come, bringing the entire population into the brave new world.

Consider the final scene. Sanjuro kills his enemy, the samurai Muroto, with a single move and blood erupts like a geyser from Muroto. His body falls into the dirt and whatever blood is left in his body pools out into the ground. Perhaps that is his eventual end as well, but it is not entirely likely.

In the coming years, 1868 to be exact, the era of the Tokugawa Shogunate ends. The Emperor is restored as the head of state in Japan with the beginning of the Meiji Restoration. And it is the samurai class who take the change the hardest. By 1873, the Samurai of feudal Japan are gone, having been folded into the police force and the military.[3]

As Sanjuro leaves Muroto’s body at the feet of the young samurai and heads off into the hills, he leaves behind the era of the Samurai, already in it’s twilight. Japan is changing as it becomes more in tune and in touch with the modern world.

About the Author; Geoff Mosse is a working writer and artist that lives a quiet, humble existence in a heavily armed and fortified compound. His first original graphic novel, The Mick is now available for purchase on Amazon

.

References

[1] Daidoji, Yuzan, and Thomas Cleary. The Code of the Samurai: A Modern Translation of the Bushido Shoshinshu of Taira Shigesuke

Boston: Tuttle, 1999. Print..

[2] “Commodore Perry and the Opening of Japan.” U.S. Navy Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Sept. 2014.

[3] The Will of the Shogun. PBS, 5/26/04. YouTube. YouTube. Web. 22 Sept. 2014.